If you’ve read anything about the basic building blocks of storytelling, you’ve probably come across the three-act structure. If not, you’ve definitely seen it being used in your favorite novels and films, even if you didn’t realize it. As one of the oldest and most reliable plot structures in the world, the three-act story structure has been the foundation of some of our most beloved stories throughout literature.

Let’s dive into why this narrative structure works in writing, some three-act structure examples, and how to begin applying it to your own work.

What is the three-act structure in writing?

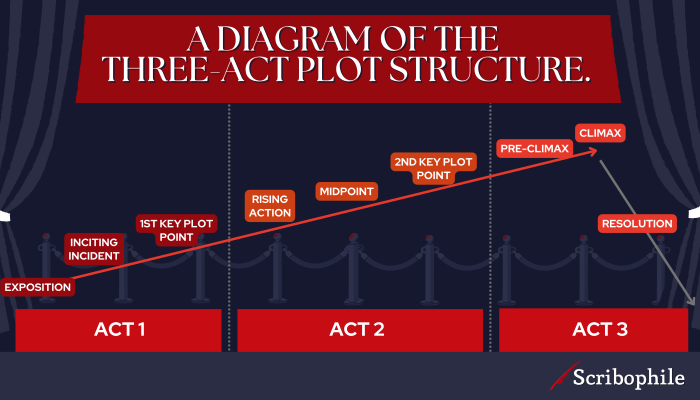

The three-act story structure is a narrative arc composed of three acts forming a beginning, middle, and end. The first act introduces the central characters and conflicts; the second act explores the way the central characters react to these conflicts; and the third act reveals the repercussions of these reactions and choices.

Each of these acts are divided further into essential plot points, which we’ll look at in more detail below.

This familiar structure takes us through the self-discovery and growth of the main characters, from landing in a strange new world (literally or metaphorically) to mastery of it. This is where we get our character development and character arcs.

The standard three-act structure as we know it today can be traced all the way back to Aristotle, a Greek philosopher who’s been credited as the grandfather of storytelling. It was his treatise on narrative structure that introduced scholars and writers to the three-act story structure.

What’s the difference between three-act structure and story structure?

You may hear writers talking about both three-act structure and story structure, but they’re not interchangeable. The three-act structure is a type of story structure. In fact, there can be many different story structures; the three-act structure is one of the most commonly used and universal story types. However, there is also the five-act structure, dramatic pyramid (or Freytag’s pyramid) story structure, the hero’s journey structure, and others.

You’ll find many of these narrative types overlap, because the shape of a good story is a universal concept that exists instinctually within us. However, story structures give both new and experienced writers a way to make sure they’re hitting the right story beats and turning points in ways that will keep readers engaged from beginning to end.

Do you need to use the three-act structure in your writing?

Some new writers might feel nervous about applying story structure to their work, because they’re worried it may inhibit their creativity. This is not the case; using structures that have been shown to work throughout history can actually free your creativity and give your story direction when you’re not sure where to go.

The three-act structure works because it mimics the shape of the stories we naturally tell each other. To be satisfying, even short stories need a beginning, a middle, and an end.

You don’t need to consciously use the three-act structure in your story—you’re should look at all different types of structure and plotting techniques to find the one that works best for you—but you’ll often find that most stories follow the three-act structure even if it’s not done consciously. That’s because it’s the most natural path for a story to take.

The three-act story structure, explained

Now that we know why this ancient narrative technique is so beloved by writers, let’s break it down into its essential elements and what each act of your story needs. We’ll look at The Hobbit, a well-known and well-loved work of literature, to illustrate each essential mechanism of the three-act structure.

Act I

This is sometimes called the “setup” act, and it lays the groundwork for the conflict and revelations to come. It takes up roughly the first 20% of your plot. The first act is made up of three core parts that lead the reader into your story.

Exposition

Your story begins with exposition, or the foundation of your story world. This is where the reader learns who your protagonist is, where they live, and what their “normal world” looks like. It will generally take up between 5% and 15% of your story, but you can sneak in world building and backstory later in the narrative, too.

Exposition is essential in helping your readers understand why your characters make the choices that they do.

In The Hobbit, the exposition shows us what a hobbit is, where Bilbo Baggins lives, and what sort of perspective he has on the world around him.

Inciting incident

This is the moment where your protagonist’s life changes forever. It might be quiet—such as a stranger showing up at the local tavern and ordering a drink—or it might be loud—such as a natural disaster that forces the main character from their home.

In some way, large or small, the main character will be pulled out of their comfort zone and set on a new path unlike any they’ve known before. This plot point can happen anywhere between the first 1%—20% of your story.

In The Hobbit, the inciting incident is when Gandalf and the dwarves invite Bilbo to come on an adventure with them. He struggles with his own natural apprehension, but agrees.

First key plot point

The first major plot point is when the story’s main character begins to engage with their new path. Although the inciting incident has already happened, in many cases it could be ignored or dismissed.

The first key plot point represents the first major turning point of the story, and shows the hero accepting their new circumstance by taking action towards it. This will usually happen at the end of the first act, about 25% of the way into your story.

In The Hobbit, the first key plot point happens when Bilbo discovers the dwarves have left without him. In this moment he could have chosen to go back to sleep, but instead he runs out to join them and begin his new adventure, leaving his everyday life behind.

Act II

Sometimes called the “confrontation act,” the second act forms the bulk of your story—from about the 25% mark to 75%, or the second and third quarters. This is where the complexities of your characters, conflicts, and themes will evolve through the events of the plot. It is also made up of three core parts.

Rising action

As the second act begins, the protagonist comes across other characters and makes new friends, faces new enemies, and overcomes new challenges.

This is where your core characters face obstacles that inhibit the path to wherever they’re going, be that a physical place or some sort of internal transformation (often both). These are the events leading to the shocking, pivotal midpoint, which we’ll look at next.

This section begins around your 25% mark and continues up until the start of the third act.

In The Hobbit, the rising action involves encountering hungry trolls, facing giant spiders, and being captured by elves.

Midpoint

The midpoint is the hinge on which your story hangs, and represents a concrete before and after for the protagonist. The main character’s goal may shift or evolve into something new.

In some ways, it’s like a second inciting incident. A significant event takes place that directly impacts the protagonist’s journey in a new and surprising way. This will happen—surprise!—at the midpoint, or 50% of the way through your story.

In The Hobbit, Bilbo becomes separated from his company and is forced to defend himself in a battle of wits. This leads to him discovering the ring of power, which makes him invisible and earns him the respect of his new friends.

Second key plot point

Just as your heroes think they’re getting things under control, the second key plot point sends them careening off into a new direction. This forces them to recalibrate and take stock of what they have to lose. The hero reflects on how far they’ve come, and how far they’re willing to go. This will usually happen at the end of the second act, or around the 75% mark.

In The Hobbit, the second key plot point that changes everything is when the dragon Smaug destroys the Lake Town, turning the people against Bilbo and the dwarves.

Act III

The third act is the culmination of the main conflict and everything that the heroes have faced on their journey. The protagonist’s goal is finally within reach. During the last act, battles will be waged, triumphs celebrated, losses mourned, and loose ends tied off.

This final act comprises the final quarter of the story, or from the 75% point to 100%. It’s also made of three essential pieces.

Pre-climax (or false climax)

Sometimes called “the Dark Night of the Soul,” this is the protagonist’s first experience in facing the antagonist head on and taking a hard look at what’s truly at risk. This will usually happen about 80%—85% of the way through the story.

Sometimes, this plot point will function as a “false climax”—the hero will defeat the villain and for a moment, it will seem like the story’s over… only to discover that the real final battle is still headed their way. It’s the moment that gives them one final push towards the story’s true climax.

In The Hobbit, this happens when Bilbo steals the precious Arkenstone and gives it to the Lake Town, hoping for peace. This causes his company to ostracize him and only makes things worse.

Climax

The climax is the showstopper of literature—the moment when everything burns the brightest and the heroes are pushed to their ultimate limit.

Everything in the plot, right from the inciting incident, has led to this moment. This is where everyone, heroes and villains alike, knows that it’s all or nothing, now or never, that the choices they make in these moments will make or break their entire journey. Your protagonist will emerge victorious, or they won’t emerge at all. This will usually happen at around 85%—90% of the way into the plot.

In The Hobbit, the climax is the epic Battle of Five Armies as all the characters of the story finally come together.

Resolution

Sometimes called the “denouement,” this section shows what happens when the dust of the climax settles and the characters move forward into the rest of their lives. They return to the ordinary world of their everyday life, but with a new perspective.

All the loose ends are tied off, lessons are revealed, and the reader is given a glimpse into what the future holds. This will take up the last couple of scenes in your story, beginning at around 95% through.

In The Hobbit, Bilbo is forgiven for his betrayal and takes his share of the treasure home to begin the next chapter of his normal life. Years later, a dwarf visits him and they recount their adventures together.

An example of the three-act structure from literature

Let’s look at one more literary example of the three-act structure. A great story that uses these three acts is Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Let’s look at how to apply it to this narrative model.

Act I

Exposition: Within the first scene, the reader is introduced to the family, the upper-class English setting, the problem of their impending eviction, and the dynamic between each character.

Inciting incident: The arrival of two handsome new bachelors in a nearby estate sets an irreversible chain of events into motion.

First key plot point: Bingley, Darcy, and company depart from the estate to return home, leaving poor Jane Bennett bereft.

Act II

Rising action: Jane goes to London to investigate under the guise of visiting family, and Elizabeth grows closer with Mr. Wickham. She meets Mr. Darcy by chance.

Midpoint: Darcy proposes(!). And in return, Elizabeth shoots him down(!!). Their relationship and understanding of one another is changed forever.

Second key plot point: Fast-and-loose Lydia Bennett absconds with Mr. Wickham, bringing shame upon the family.

Act III

Pre-climax (or false climax): Lydia and Mr. Wickham return properly married; Lydia reveals that Darcy orchestrated the entire thing and paid off her hapless new husband. Bingley and Jane are reunited, and it looks like everyone is set to live happily ever after.

Climax: Darcy gives himself one last shot at securing Elizabeth’s love and proposes. This time, she accepts.

Resolution: The Bennett family is thrilled for the daughters, Elizabeth and Jane celebrate their weddings, and the reader gets a glimpse into their future lives.

How to apply the three-act structure to your own story

Writers work with a variety of different tools and perspectives, and no two writers will approach their stories in exactly the same way.

If you prefer to organize your thoughts into a coherent pattern right from the very beginning (a “Plotter”), you may find it helpful to work with each of the plot points in the three-act structure to develop your idea into a coherent narrative.

If you prefer to explore your story world as you go and discover new things through the writing process (a “Pantser”), you may find it more helpful to look at the three-act structure through the editing stage to help refine the pacing, character arc, and overall shape of your plot.

When you begin your work, you should try to have an idea of where your story begins (the exposition and inciting incident), the major turning point of the story and character arc (the midpoint), and where you want it all to end up (the climax and resolution). Then you can build your story outwards from these core moments.

If you’re beginning a new story, try filling out each element of the three-act structure: exposition, inciting incident, first key plot point, rising action, midpoint, second key plot point, pre-climax, climax, and resolution.

Ask yourself what you want your protagonist to learn along the way, what they need to overcome in order to reach their goal, and how each of these moments brings them closer to it or pulls them further away.

If you already have a story that you’ve written, try transposing it over the three-act structure and identify each of those key moments. Are any of them missing? Are some too close together, or too far apart? This is where you might run into pacing issues where your story lags behind or feels too rushed.

This can be a wonderfully helpful tool for ensuring that your work reads smoothly and feels like a complete, satisfying narrative.

Using the three-act structure creates stories that work every time

Many great stories have been born from these three acts. They form a pattern we’ve learned to recognize since before even the written word, dating all the way back to fireside oral traditions. By learning from these three-act stories and how they’re put together, you can create enduring stories of your own that readers will return to again and again.