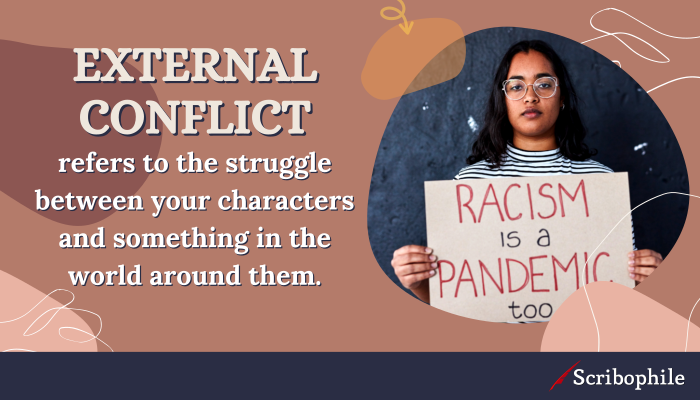

When someone asks you, “What’s your book about?” you probably sum up the plot of your story with two things: the main character, and the external conflict.

It’s about a nerdy teenager who stumbles on an illegal drug ring in his high school.

It’s about a woman trying to advance her career in a misogynistic, male-dominated industry.

It’s about a warrior who comes out of retirement to face a monster everyone thought was a myth.

A story’s external conflict is often the biggest thing readers look for when they’re choosing what to read next, and it’s the thing they’ll remember when they’re telling their friends how great your book was later. We’ll take you through everything you need to know about the different types of external conflict a story can have, how to find the right one for your plot, and some examples from successful novels.

What is external conflict in a story?

External conflict is the struggle that occurs between a character, usually the protagonist, and an outside force. The outside force might be another character, a group of people, a force of nature, or even a societal or cultural belief. External conflict forces the character to make choices that ultimately drive the events of the plot.

Sources of external conflict usually do one of two things: they either drive the plot by forcing the character to change, or they drive the plot by being resistant to change. For example, if your protagonist’s parent is faced with a sudden health crisis, the protagonist might have to change their routine and start taking on more work to support them. On the other hand, if the protagonist’s parent is refusing to give them permission to try something new, they’re creating an external conflict that is resistant to change.

In both cases, the character needs to think creatively and find ways to overcome this external problem.

What’s the difference between external and internal conflict?

Truly great stories are able to balance both internal and external conflict. The difference between the two is that external conflict comes from a character’s struggle against something in the outside world, while internal conflict is tension that originates from within the character itself—in other words, the classic story conflict of character vs. self.

An example of internal conflict might be if a character has to choose between two different paths in life, or if they’re faced with a choice that goes against their personal morals. Meanwhile, the external conflict might be the force that’s creating those choices in the first place—for instance, debt collectors, challenging family relationships, or professional rivalry.

The most engaging and effective stories will have layer upon layer of conflict that your protagonist needs to overcome in order to learn something about themselves and earn their happy ending.

The 5 types of external conflict that characters encounter

There’s no end to the challenges you can throw at your main character. External conflict comes in many forms, depending on what form these challenges take and where they’re coming from. Let’s look at the different types of external conflicts you can work with in your story.

1. Character vs. character

The character vs. character conflict happens when two characters in a story want things that are mutually exclusive to each other. You’ll probably recognize this type of conflict from the superhero genre, in which the main character is constantly battling other characters who are looking to cause trouble. Whether it’s murder, armed robbery, or just generally inciting chaos, the villain has an end goal which is in direct opposition to the hero’s goal: keeping their city safe.

This type of external conflict is one of the oldest and most enduring narratives, probably because it lends itself so well to the oral tradition. If you’re sitting around a bonfire with your tribesmates, the story of how one warrior overcame an enemy warrior from the other side of the river is more engaging than the story of how one warrior battled with himself over what to have for breakfast.

However, character vs. character conflicts aren’t always a battle between good and evil. Two good characters (or two evil ones) can want different things that put them in conflict with one another. For example, two colleagues might be competing for the same promotion, or a highschooler might be aiming to apply for a college overseas while their parents want them to apply for one closer to home.

2. Character vs. nature

The character vs. nature conflict occurs when the protagonist is faced with an impersonal force of the natural world like a tornado, hurricane, or flood. It could also be an inhospitable landscape, like being lost in the wilderness or stranded on a deserted island. In these instances, the hero of the story needs to adapt, overcome, or escape in order to protect themselves and their loved ones.

An important thing to note about nature conflicts is that the antagonistic force isn’t acting out of any kind of intentional malice. If a storm tears down your main character’s house, it’s nothing personal; it’s just going about its day, doing what storms do. This means your hero is facing something with a fundamental lack of agency and humanity… which can be even scarier than facing a murderous supervillain.

This type of external conflict is a great vehicle for character-driven stories, because the way people react in times of unstoppable crisis will reveal a lot about who they truly are.

3. Character vs. the supernatural

The character vs. the supernatural conflict became popular in the Victorian era, and still fascinates readers today. This type of conflict happens when the main character is faced with something more than the world we know—for instance, ghosts, vampires, cursed objects, and so forth (although not generally considered “supernatural,” alien races would also fall under this type of conflict).

Like the nature conflict, supernatural conflicts force the protagonist to adapt very quickly to a new way of looking at the world. Suddenly, none of the old rules apply.

This type of conflict is also very flexible. You can use it to create a fast-paced, action-packed story, or a deep, emotional exploration of what it really means to be human.

4. Character vs. society

The character vs. society conflict involves the hero coming up against a political system, societal convention, or cultural belief. The antagonistic force in these stories is a large, bodiless problem with the world that is much bigger than your main character. This makes the society external conflict similar to the nature conflict. If your story’s antagonist isn’t a government system but a single political leader, that would be a character vs. character conflict instead.

Society conflicts are very popular in dystopian literature. For example, The Handmaid’s Tale shows the protagonist fighting against a broken system designed to oppress women. However, this type of conflict can be effective in any genre to draw attention to cultural issues like racism, homophobia, gender disparity, or class divides. Stories with this conflict explore what is wrong in the world and how it might be overcome.

5. Character vs. fate

The character vs. fate conflict happens when a character struggles against their own destiny. This might be a literal destiny as laid out by a prophecy, oracle, or divination; or, it might be a social destiny, such as inheriting bad habits or bad luck from one’s family. In these types of stories, the main character wants to make their own choices, but fears there was never any real choice at all.

This conflict type lends itself well to tragedy, because the act of trying to outrun one’s fate is often the hero’s undoing. However, this can also be a good conflict to use when exploring the values of tradition vs. innovation, or heritage vs. independence.

Examples of external conflict in literature

To see how other writers have made external conflict work in their stories, let’s look at a few examples from classic and contemporary literature.

External conflict in Pride and Prejudice

A study in both external and internal conflicts, Jane Austen’s classic satirical romance pits its characters against both the social norms of the day and each other. The heavily matriarchal family is limited by society’s expectations of them and its laws: if their father dies, their home gets shuffled off to a distant male relative, instead of the five daughters who grew up there! Unable to change the rules, the main characters need to find the best possible path through them.

The novel also features several layers of character conflict, in which the main characters work towards goals that conflict and undermine each other’s. The clearest example of this is Mrs. Bennett, the head of the family, who desperately wants to see her daughters married off. Trifles like love and happiness take a back seat.

External conflict in Macbeth

One of the most famous examples of the character vs. fate conflict, this Shakespearean play follows the titular protagonist who tries to outwit his destiny. At the beginning of the story, Macbeth meets a trio of witches who tell him one day he’ll be king. Pretty cool, he thinks, so he kills poor King Duncan in his sleep and takes the Scottish crown.

Unfortunately, the witches have a couple caveats about Macbeth’s ultimate fate. He spends the rest of the play trying to outmaneuver the prophecy about his death, which, in classic tragedy form, only leads to his undoing.

External conflict in The Ocean at the End of the Lane

In one of the most powerful examples of character vs. character conflicts, Neil Gaiman’s novel sets its young hero against a villain who is more powerful than him in every way. In typical “David and Goliath” style, the protagonist struggles to overcome an adversary that seems unstoppable. The character’s journey is all about discovering his own inner strength and finding creative ways to outwit his enemy.

How to develop external conflict in your story

If you’re looking to add external conflict to your story, there are a few things you can keep in mind. A well-developed central conflict can create tension, enhance character development, and keep readers engaged every step of the way.

Consider what’s at stake

For your story’s external conflict to be effective, your character needs something to lose. They need a good reason to stand and face the conflict, rather than turning tail and making a fresh go of it somewhere else. What’s really at the heart of the problem?

If we look at Pride and Prejudice, above, Mrs. Bennett and her daughters are at loggerheads over Mrs. B’s need to get her daughters safely shacked up. But, it’s hard to deny that the dame has a point: if her daughters don’t find a husband—any husband—they’re going to end up living in a cardboard box.

Often in life, the easiest way to avoid a conflict is to simply walk away. But, if your character walks away, there’s no story. Ask yourself what’s keeping them there and what they stand to lose.

Consider your character’s strengths and weaknesses

The best external conflicts occur when they play off the protagonist’s inherent strengths and weaknesses. The core conflict will force the character to face the weaknesses that have been holding them back, and discover new strengths they didn’t know they had.

For example, if your protagonist is very shy and introverted, the story’s conflict might be something that forces them to speak up against oppression. Or, if your character is someone who is physically very strong, they might come up against someone even stronger and have to look for creative new ways to defeat their enemy.

A good story is all about growth and discovery, so the story’s conflict should make the main character challenge themselves in ways they never expected.

Consider your story’s internal conflict

A story’s internal conflict is just as important, if not more so, than its external conflict. Truly compelling stories balance both and use them to inform each other. Your story’s external conflict might create an internal struggle for your character, or their internal struggle might lead to an unexpected external conflict.

For example, maybe your character is struggling with the inherent ethics of their workplace. That’s an internal conflict. But their uncertainty could lead to secondary conflicts like a falling out with a coworker, a financial crisis if they lose or leave their job, or a societal conflict as the protagonist begins a movement against the company. This can lead to even more internal conflict as they consider whether or not they’ve done the right thing or deal with the guilt of letting down others.

When developing the external conflict of your story, think about how it affects the main character’s mental well-being and their relationships with those around them.

External conflicts move the plot forward

External conflict occurs when characters struggle for or against change. They either want something to be different, or external forces are making things different and your protagonist doesn’t like it. In either case, the threat of change or stagnation pushes your characters to make choices—and choices are what carry your story.