There’s something undeniably cathartic about the tragic hero figure. From ancient Greek performances to contemporary film and everything in between, these complex, emotionally resonant characters have entertained audiences (and taught them valuable lessons) for generations.

So what exactly do we mean by a “tragic hero”, and how do they compare with other archetypal characters? Read on for everything you need to know about how we define the classic tragic hero, with some examples and tips for writing your own.

What is a tragic hero in literature?

Tragic heroes are protagonists who fall from a state of nobility, privilege, or good fortune due to an insurmountable personal weakness. They exhibit enough virtue, compassion, or other traditionally heroic traits to make them relatable and empathetic, but meet a tragic end once their fatal flaw gets the best of them. These heroes act as cautionary tales to the audience.

For example, a tragic hero might be a main character who does everything right, but ultimately loses everything once he chooses ambition over love. Or, like Romeo in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, chooses the thrill and novelty of young love over common sense.

These characters make readers want them to succeed. And yet, we watch as they hurtle to their heartbreaking, inevitable conclusion. Their stories help us understand what happens when we allow our own weaknesses to consume us.

What’s the difference between a tragic hero and an anti-hero?

“Tragic hero” and “anti-hero” are literary terms that sometimes get conflated, but they’re not quite the same thing. You can think of a tragic hero and an anti-hero as reflections of each other: while tragic heroes are basically heroic figures with one toxic, devastating flaw, anti-heroes are figures who lack traditionally heroic qualities but are underpinned by an internal strength.

An anti-hero might be physically weak, unethical, cowardly, or self-serving. In spite of this, they demonstrate the potential for redemption and growth. Tragic heroes warn us that weakness exists even in the most promising of people. Anti-heroes show us that strength can be found even in the most unlikely of places.

Characteristics of the tragic hero

Let’s look at the key character traits that every literary tragic hero needs.

Nobility

To begin, the tragic hero needs to come from a place of elevated status. They don’t need to be of literal noble birth (although this was often the case in the classic Greek tragedy, as well as in Elizabethan plays, because… don’t we all love to watch posh people behaving badly?); however, they do need to be ranked above the “average person” in some way.

They might be the most popular kid at school, or employee of the month at their job, or a prominent social media influencer, or the beloved eldest child in their family. Whatever their social parameters might be, their journey opens in a place of “This person has their life together.”

Empathy

Despite the character’s elevated status, they should have enough endearing qualities that the reader wants them to succeed. They might be very kind, or charming, or they tell great stories at parties. Make sure the reader sees the humanity in this character to develop their compassion for them. Without the audience’s sympathy, the hero’s tragic downfall wouldn’t be tragic… it would just be satisfying.

A tragic flaw

Ah, the rotten core of the tragic hero’s downfall: the fatal flaw. This is the character’s one irreconcilable vice which ultimately leads to their undoing. Ambition is a common tragic flaw, but it could also be something like jealousy, insecurity, cowardice, or a desperation to be loved.

These fatal flaws will guide the hero forward, pulling them mercilessly towards their inevitable conclusion.

Drive

Like all literary protagonists, the tragic hero needs to want something. Their lives are going pretty great so far, and they would be perfect if they could only attain that one thing. A better title, a bigger house than their annoying neighbor’s, more followers, more respect, the right person to fill that emotional void.

Their pursuit and subsequent obsession for this one thing is what carries the plot of the story and erodes the character’s pristine life into a dumpster fire of regret.

Conflict

Finally, like all good storytelling, the tragic hero needs conflict. Specifically, internal conflict that has them battling themselves as they hurtle forward along their damaging path. Consider Shakespeare’s Macbeth (whom we’ll look at in more detail below): he doesn’t really want to stab anybody to death, but wouldn’t life just be so much better if he was king? Plus, it’s clearly Lady M who wears the pants in that relationship.

Internal conflict helps elicit sympathy in the reader, because we can see the path the character could have taken. This makes their downfall even more tragic.

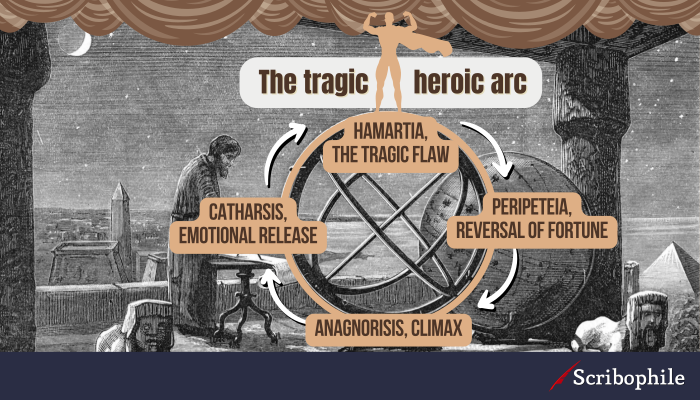

Elements of the tragic hero’s journey

The Greek philosopher Aristotle—a dude who knew a thing or two about the foundations of narrative—coined what he called the “pillars of tragedy”: elements that every tragic hero’s journey should have. These terms are useful to know when it comes to understanding the structure of a tragedy (and impressing your friends).

Hamartia

Hamartia is the traditional term for the hero’s fatal flaw or weakness. The word means “to err,” or “to miss the mark.” This is a characteristic or personality trait inherent in the protagonist which, when left unchecked, grows until it takes over the protagonist’s life completely.

Peripeteia

Peripeteia means “reversal of fortune.” It’s the moment in a story when things start going downhill— fast. Although the hero hasn’t yet been completely overtaken by their fatal flaw, the reader will have a sense that the main character is starting to lose control of their carefully curated life.

Anagnorisis

Anagnorisis is a word that means “recognition,” and it’s usually the climax of the hero’s tragic arc. It’s when the main character is confronted by the reality of how spectacularly they screwed up, and are forced to acknowledge that they really only have themselves to blame.

Catharsis

Catharsis is a term that refers to the reader or audience’s experience with the tragic hero’s story. It’s the emotional release, or cleansing, that comes from watching the hero’s downfall. This emotional release encourages the reader to reflect on the experience and the relationship they might have to this weakness in their own lives.

Examples of tragic heroes from literature and film

Let’s look at how these traits play out in some popular examples of tragic heroes.

Shakespeare’s Macbeth

Macbeth (or The Thane, if you’re an actor) is one of literature’s most famous tragic heroes. He’s basically a decent bloke, except for his relentless ambition. When Macbeth hears a prophecy from a trio of witches promising that he’ll one day be king, he decides to take matters into his own hands (with some encouragement from his steely-eyed wife).

Despite his success, Macbeth doesn’t have the heart of a murderer, and his guilt and grief weigh him down. Once he achieves power, however, he becomes desperate to hold onto it. His increasing ambition and subsequent paranoia ultimately lead to his undoing.

Don Draper from Mad Men

Mad Men is a television series that follows a toxic ad agency in the 1960s, and its suave, polished protagonist Don Draper may be the maddest of all. Early in the show it’s revealed that “Don Draper” is actually a stolen identity, and the man’s entire life is a façade. The fatal flaw of this modern tragic hero is his pride, and through that pride, a need to control everything and everyone around him.

Naturally, this fist-clenching approach to life does more harm than good; it eventually pushes away his friends, family, and professional relationships. By the end of the show’s seven-season run, his actions towards others have led to a nervous breakdown and complete isolation from everyone who used to believe in him.

Oedipus from Oedipus Rex

This iconic Greek tragedy by Sophocles is one of the most formative plays of all time, and we can see echoes of its themes and structure in Shakespeare’s work as well as in contemporary literature. Th title character Oedipus is a respected king who, like Macbeth, is waylaid by a perplexing prophecy: he’s fated to kill his father and marry his mother.

As one would expect, his parents aren’t thrilled with this, so they abandon their baby to the wild elements. Except of course Oedipus does grow up, never knowing who his real parents were, and you can probably imagine how swimmingly that goes.

Oedipus’s fatal flaw is his hubris: he believes himself to be above the constraints of destiny (and, thereby, above the gods). When he learns of the prophecy, he spends the rest of the play trying to outrun his fate—which, because this is ancient Greece, is exactly what sets his fate into motion.

How to write your own tragic hero

Ready to develop your own tragic hero (or tragic heroine)? Here are the essential character-building steps to take as you explore your story.

Develop your hero’s ordinary world

First, you need to develop your tragic hero’s everyday life—specifically, what they have to lose. This means their relationships, accomplishments, social network, and so forth.

Remember, your protagonist should begin from a place of relative nobility to those around them so that the reader has a sense of how far they have to fall. In order for your hero’s arc to be truly tragic, there needs to be a clear and dramatic decline in fortune. Show your reader what your hero is most proud of before you take it all away.

Isolate your hero’s tragic flaw

Your protagonist is probably a reasonably upstanding dude(ette)… except?! What’s the one weakness they’ve never quite been able to overcome? What makes them feel unsatisfied with their current state of being?

Ambition, paranoia, cowardice, casual cruelty, avarice, excessive pride, self righteousness, and internalized prejudice are all potential fatal flaws (or hamartia) that might prove to be your hero’s undoing.

Determine what they’re fighting for

Once you know what your hero’s tragic flaw is, determine what this flaw is driving them to do and how they’re using it to fill a perceived void. They might be working towards a promotion, a milestone number of Instagram followers, a relationship with the perfect man or woman, authority over their circumstances, or some other benchmark that will make them believe that they’ve “arrived.”

This pursuit of something they believe will make them happy (even though it probably won’t) is what drives the story’s plot, leads to the hero’s suffering, and ultimately brings about their own destruction.

Lead them to a reversal of fortune

That’s the peripeteia, remember? The hero’s quest is steadily gaining ground, until it suddenly skids dramatically off course. It might start with something small going wrong—a miscalculation, a misunderstanding, a bad review, one bad choice—which then snowballs as the tragic hero responds to the event and starts making things a lot worse.

Now, the hero has to scramble to regain the control they once had as the ground starts to crumble beneath their feet.

Watch them crash and burn

The hardest, yet most satisfying, thing about watching the tragic hero’s life collapse is knowing that their fate was sealed almost from the beginning. Once the protagonist proved that they were unable to rise about their fatal flaw, it was only a matter of time before they lost their grip and descended into a hell of their own making.

This is where the catharsis comes in. The reader or listener is able to learn from the hero’s mistakes and reflect on their own weaknesses and strengths.

In literature, tragic heroes make us think

In an age when hope and positivity is more important than ever, does storytelling still have a place for tragedy? Tragic heroes remain resonant and effective because they teach valuable lessons and help give readers (and writers!) an emotional release. With these tips, you can take readers on their own tragic journey—and then safely close the page once it’s over, no Oedipal eye-gouging required.