Stories are gloriously, beautifully unique; there are as many of them in our world as there have been storytellers. Although many stories follow classic story archetypes, each one is its own distinctive act of creation.

But even though every tale is one of a kind, we can still see patterns in what makes our favorite stories engaging and memorable. These patterns are where we find our essential story elements.

What are the elements of a story?

The elements of a story are the core building blocks that almost any narrative will have, whether it’s a short story or a series of novels, a literary coming-of-age saga or a science fiction epic. These include: a protagonist, an antagonist, setting, perspective, an objective, stakes, rising action, falling action, symbolism, language, theme, and verisimilitude.

It’s these key elements that make us care deeply for the characters, their journey, and the lessons they learn along the way. They’re what make us take the journey and learn those lessons right beside them.

Let’s take a look at the basic story elements you’ll see again and again in the stories we love, and how to use all these elements when writing your own original tales.

The 12 essential elements of every great story

All great stories can be broken down into twelve basic elements. Here’s a closer look at each one and at why they’re so integral to crafting a good story.

1. A protagonist

A protagonist is the central character within a work of literature. A book is always told from this character’s perspective (we’ll look more at perspective down below).

They’re the beating heart to which all roads lead, the one whose choices carry the plot to its conclusion. All other literary elements and devices including the antagonist (which we’ll look at next), environment, and conflicts will in some way support the protagonist’s journey.

These things might help them along their way, become an obstacle that the protagonist needs to overcome, shape who the protagonist is and their relationship with the world around them, or challenge that relationship and teach the protagonist something new. No matter what, everything in your plot structure should in some way be connected to your central guiding character.

A great protagonist is particularly important because they’re the lens through while your reader will see the world of your story. It’s through their triumphs, losses, joys, passions, and agonies that we live within your world and come away from it slightly changed—with a new perspective or a new understanding about what it is to be human.

For tips on how to write a great protagonist, check out our lesson on character!

2. An antagonist

In order for your protagonist to go on a journey—which maybe a physical journey, or an emotional or spiritual one—they need someone or something to challenge them into action. An antagonist is a story element whose goals stand in direct opposition with the goals of the protagonist. They want something, and the protagonist wants something, and those desires cannot exist within the world at the same time.

Most classic villains are antagonists, but an antagonist can also be an otherwise good person whose circumstances have put them in conflict with the central character. They might even be a friend or loved one who has made different choices or has a contrasting view of the world—for example, a parent who can’t agree with their child’s plans for the future, even though the choices they make come from a place of love.

An antagonist can also be more than one person—for instance, a collective group, society, government, or culture. The protagonist’s major conflict may also be something impersonal, such as a force of nature, or it might come from within, like a mental illness or a weakness such as addiction.

Conflict can come in many forms. What matters is that the trajectory of the antagonist or conflicting force forces the protagonist into action and carries the story’s plot forward.

You can find out more about antagonists in literature, and how to craft a dynamic, compelling villain, here.

3. Setting

Setting is the time and place where your story happens. It refers to both the physical location of your narrative and the way your characters are affected by their time and place: their cultural environment, their relationship with the natural world, the way they speak, what sort of social and political events are happening around them.

All of these things are a part of how your characters formed as people.

This can play a major role in the action of the plot. If, for example, your novel is a horror story that takes place in a haunted house, the setting becomes the crux of every choice that your protagonist makes. If your book takes place during the Jazz Age of the American 1920s, the time period and its predominant cultural values will play a huge part in how your characters react to the world around them, what their limitations are, and the way in which they challenge those limitations.

Choosing the right setting and bringing it to life gives your writing a whole new dynamic. It’s where character, choice, and action all begin.

Want to learn more about writing engaging, vivid settings? Check out our lesson on setting.

4. Perspective

Closely tied to setting is perspective, or the way your characters see the world. Every one of us brings our own unique filter to the relationship we have with the world around us, built out of our cultural biases, class, social interactions, level of education, upbringing, belief system, and experiences.

If you’re writing a work of medieval historical fiction, for instance, one character’s perspective can vary enormously from another’s. You could show your reader a single scene from the point of view of a queen, a servant, a young child, a landowner, and a knight and produce a very different story within every single one. Even in modern-day fiction, things such as race and social class still have an impact on how we build the world in our mind.

Perspective can also refer to point of view, or the specific narrative lens you choose for your work. The most common points of view in fiction are third person and first person, but there’s also second person and fourth person point of view to choose from! You can learn more about each of these types of point of view in our writing academy.

When used correctly, perspective is a marvelous literary device for bringing depth and suspense into your writing. It’s through clever use of this story element that we get things like the unreliable narrator, in which the writer deliberately misleads the reader’s expectations by writing from a skewed or uninformed point of view.

5. Something to fight for

When we looked at protagonists and antagonists we saw how these two central characters always have opposing goals. When forming your idea out of these basic elements, it’s essential that your hero has something to work towards. Your characters’ goals are the things that will power your story from beginning to end.

This might be a tangible objective, such as the quest for the holy grail; or it might be something more internal, like repairing a damaged relationship. In a good narrative, every single character should want something or be striving for something all the time—however, it’s the goal of your protagonist that’s going to drive the story forward.

Their choices, the consequences of those choices, and their subsequent reaction to those consequences will all be connected to their primary objective: the thing they have been fighting to reach all along.

6. Something to lose

Here’s where your story begins to develop its layers. Your protagonist needs something to fight for, but they also need something that’s at risk. Something they stand to lose if they fail in reaching their goal.

Let’s say your main character really, really wants a new car. That’s an objective—something to fight for. But what happens if he doesn’t get it? Probably not much. He’ll have to keep taking the bus to work, and he might swoon longingly as he passes by the auto dealer on his way home, but life will more or less go on the way it always has. That’s not enough to create a compelling story.

Unless… unless he lives in a rural area where there’s no public transportation, and he’s looking to buy a new car because his has broken down. If he can’t replace his car quickly he won’t be able to keep his job. If he loses his job, he probably won’t be able to keep supporting his family and he might even lose his home. Suddenly wanting a new car is a much more urgent and complex issue.

Your protagonist needs a reason to want the things they do, and to be aware of consequences (real or imagined) if they aren’t able to get them in time.

7. Rising action

When we get into the structure of our plot, the rising action is the escalating cause and effect that comes from the characters’ choices. Every time your protagonist does something in pursuit of their goal, their action will trigger effects in the world around them—some anticipated, some not. At the same time, your antagonist or antagonists will also be pursuing their own, conflicting goals, making their own choices, and sending even more effects out into the world. It’s this interplay of choices, consequences, and reactions, growing greater in urgency and intensity, that builds the narrative arc as the plot unfolds.

To learn more about how to structure your plot from inciting incident to epic conclusion, check out our detailed lesson on plot.

8. Falling action

Once your plot has reached its climax, and your protagonist has finally obtained their goal (or not), and the antagonist has been defeated (or not), and the world as it was has crumbled and then been rebuilt into something new, it’s time for your falling action. Many writers make the mistake of ending their story too quickly, but your readers need time to see the new landscape as it comes together and to say goodbye to your characters after the story’s resolution.

This section won’t take up a huge amount of real estate—usually about ten percent of the book at most. This is where you take a little bit of time to explore what it means to your protagonist to have reached this place in their journey, how those around them are affected by it, and—this is important—where they’re heading next. This gives your reader time to absorb the messages in your story and the lessons they have learned.

9. Symbolism

Symbolism is using an object, place, person, or element to represent something other than its literal meaning. Even a small thing can represent a big idea. In a story, symbolism can be a recognizable universal symbol or it can be a symbol that’s developed within the context of your world.

Symbolism gives depth to your story and helps support the theme (we’ll talk about theme a little farther below). Contextual symbols, in particular, help convey the message that you’re trying to send through your writing. For instance, if you’re exploring the idea of enduring love through times of great hardship, you could work symbolism into your story by using a fragile object such as a teacup, a vase, or a figurine which manages to stay intact despite being dropped or knocked around. This then becomes a symbol of a relationship that is more durable than it would appear in spite of the dangers it might face.

Very often readers will absorb symbolism in your writing without consciously realizing it. They may not see that the object was a cleverly placed literary device, but they’ll feel the tension and tone it creates in parallel with the plot.

We’ve got lots more detail on how to incorporate rich symbolism into your story here!

10. Language

In writing, language is the tone, mood, word choices, sentence structure, and unique author’s voice that pulls the story together. Some authors, like Ernest Hemingway, are famous for short, clean lines with simple words and no ornamentation. Others, like Joanne Harris, favour more languid sentences full of delicate flowering words and sensual imagery. Edgar Allen Poe is famous for his dark, velvety vocabulary that brings to mind gothic castles and stormy nights, while writers like Jane Austen use light, approachable sentences peppered with sardonic undertones that go on for half a page.

While many writers will grow to develop a distinctive voice of their own, they may also adjust their rhythm and tone to fit the mood of the type of book they’re writing. In general, shorter, more monosyllabic sentences will speed up the pacing while longer sentences slow it down. Beach reads and thrillers tend to rely more on the former, while historical and literary fiction often use more long sentences. A mix of both is best—too much of either one gets difficult to read for very long.

When exploring language, think about the mood and images you want to convey with each scene. Then see if you can choose the lengths of your sentences and the types of words to match.

To learn more about using unique, beautiful language in your writing, have a look at our lesson on developing your writer’s voice.

11. Theme

Theme is the point of your story. It’s the central idea or message that you’re trying to send your readers through the filter of a fictional world. This can be something like the unbreakable bonds of family, the ravaging landscape of social media, or the seductive destruction of avarice. You may think of a message that you want to explore and build a plot around it, or you may begin writing a story and uncover its true meaning as you go along.

Once you know what the theme of your story is, you can emphasize it further using a range of literary devices including symbolism, metaphors, and allegory as well as your cast of characters and the types of conflicts that they face. Each element of your story should support this central message in some way. By showing the power of this message and the effect it has on the characters and the world, you can make the reader understand its importance and inspire a very real change. That’s the power of storytelling.

You can find out more about how to develop your own themes in our lesson here.

12. Verisimilitude

Verisimilitude comes from a word that means “truth,” and it means the truth within a fictional context. All powerful stories come from a true place—from real human needs, strengths, weaknesses, and experiences. This is equally true, if not more so, in fantastical work. If you’re writing about a man who gets exposed to gamma radiation and becomes a big green smashing machine, you’re then asking your reader to accept that this is the truth of your story: stay away from gamma radiation. It’ll Jekyll-and-Hyde you up. Even when you and your reader both know, deep down, that this isn’t actually what gamma radiation is in the slightest, they accept it as the basis of this particular reality.

This comes down to verisimilitude. Even though you’re showing the character in a fantastical and frankly ridiculous context, what stays with us as readers are the deep, sometimes uncomfortable truths: don’t we all have polarities inside of us that make us question who we are? Does Bruce Banner secretly want to be a stronger, braver, more unfeeling version of himself? Wouldn’t you? It’s these intimately resonant connections, more than an iconic pair of tattered purple shorts, that form the heart of this narrative.

When telling a story, no matter how absurdist or unrealistic or removed from our world it may be—especially then—figure out how to offer it to your readers from a place of honesty and truth.

Elements of a story in literature: examples from 5 enduring stories

All the tools we’ve looked at are present in every great story that has been handed down to us through the years, as well as inspiring new works of art that are still being produced today. The ones that stay with us most are the ones that use these elements in surprising new ways. Let’s look at how these patterns function in our best-loved works of classic literature.

1. To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee

Harper Lee’s renowned novel is set in a fictional American town in the 1930s, though it could easily be in any of a hundred very real places in just about any time period—even today. In this story a black man is falsely accused of rape, and the consequences of that accusation radiate outwards to affect the lives of the people in the story. The novel’s powerful conflict—which was very much influenced by its setting, and its innate prejudices and limitations—communicated a theme which encouraged readers to look at their own history, their ideas, and their future in a new way.

The novel both makes use of and challenges the perspectives of the time. The first-person narrator of this novel is a young child who struggles with her own prejudices and expectations of cultural norms. Through the narrative we see her perspective change as she grows to understand the battles faced by other people and the need to look at every human being as an individual. This juxtaposition of a young central character with a very grownup central conflict creates a powerful theme that has stayed with us for decades.

2. The Maltese Falcon, by Dashiell Hammett

Like many noir thrillers of its time, this classic novel by Dashiell Hammett is heavily driven by the surprising twists and turns that make up its rising action. It’s told through a third-person narration that follows an array of people, many with questionable moralities, who are fighting for their claim to a mythical lost statue. The Maltese Falcon also gives us some of the thriller’s signature character archetypes: the protagonist Sam Spade, the jaded, smooth-talking private eye that would go on to influence the staple hero of the genre. We also have the femme Brigid O’Shaughnessy, one of the novel’s central antagonists, who gave birth to an archetype of seductive, deceitful fatales.

The plot is propelled forward by one mounting conflict after another, set against the backdrop of its distinctive setting: a dark, gritty San Francisco in the late 1920s, in the decade’s height of roaring decadence just before its fall into the great depression. The iconic characters combined with the vivid backdrop have given us a formula that has engaged readers for generations, and will continue to do so for generations more.

3. Breakfast at Tiffany’s, by Truman Capote

Now inextricably associated with Audrey Hepburn’s trademark black dress, Truman Capote’s 1958 novel is built strongly out of setting and character. The central character, Holly Golightly, comes from a modest and scattered upbringing to explode onto the social season of New York’s glittering upper east side. Holly is at odds with her time and place, a city and a decade in which women were expected to conform to patriarchal expectation. Nearly everyone she interacts with attempts to curtail her freedom and independence, which causes that freedom to become something of a contrarian obsession.

It’s this series of small, mounting interpersonal conflicts that support the real conflict of the plot: the main character’s fight for independence to the point of self destruction, and her need to express herself in a larger society that represses expression of the self. This is a perfect example of the power of verisimilitude in a novel: every one of us has fought a similar internal battle at some point during our lives, and we can identify with her struggles to unite her opposing needs and desires.

4. The Lord of the Rings, by J.R.R. Tolkien

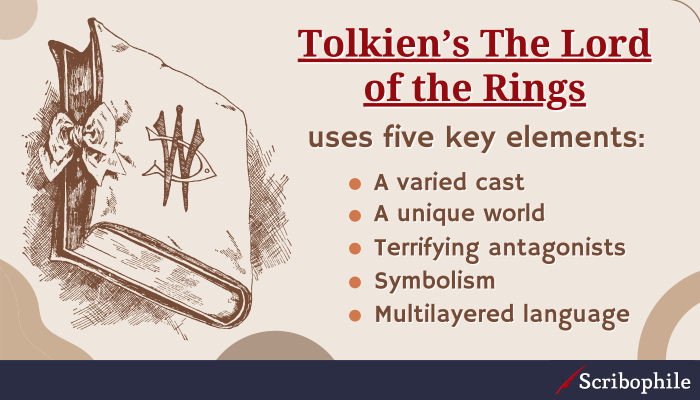

J. R. R. Tolkien’s magnum opus has all the elements of a story sprawled across an epic, magnificent canvas: a varied and expressive cast of large and small heroes; an entirely new, unique world; terrifying antagonists; a rich tapestry of symbolism and themes; and an ambitious use of multilayered language that hasn’t been matched since.

While every one of these story elements plays an important part in this saga, the one that probably stays with readers the most is its setting—a multifaceted landscape of Tolkien’s creation with its own histories, languages, cultures, traditions, and races of people. The author accomplished the extraordinary feat of creating an environment that felt like home for generations of readers. It also went on to inspire a myriad of other stories in the modern fairy tale genre.

It’s worth mentioning how well this series utilizes its falling action, the events following the enormous conflict that has powered the events of the plot. Tolkien takes time to show us who these characters are outside of the battles they’ve faced, and where their path is going to lead them next. It’s arguable that seeing how these characters return home, changed by their experiences and embracing a new beginning, has endeared them to their readers most of all.

5. A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens

One of the most famous character-driven novels of all time, this story centers on an irascible protagonist who faces the most complex antagonist of all: his own mistakes. Set in Dickensian London, this novel takes the protagonist through several powerful settings, each with a strong personal connection. Through these settings we get to see the supporting characters, people in the protagonist’s life who show him his comfortably embraced weaknesses and his uneasily discarded strengths.

Although the main character, Ebeneezer Scrooge, is a personality so powerful he borders on caricature, he shows us what we could become if we allowed fear and avarice to devour us. The novel shows us what the protagonist is fighting for—a second chance to be a better man—and what he has to lose if he fails: his immortal soul. This story uses symbolism and strong thematic elements as the story unfolds to send a powerful message of redemption and free will to the reader. This is a good example of how the conflict your protagonist faces directly supports the theme that you’re trying to convey.

Using the elements of a story to strengthen your writing

Your own work in progress might have some of these important elements already, and you can emphasize them even further to connect more deeply with your reader. Consider your main characters, location, and the conflict or conflicts that drive the plot forward. Explore your story’s perspective by looking at the way the setting have informed your protagonist’s view of the world. What sort of prejudices, theologies, and values have they absorbed as they grew into the person they are today?

Once you uncover these you’ll start to see glimmers of your theme hiding underneath the surface.

When you begin to understand the theme of your story, you can then begin forming more layers with symbolism, unique settings, and relationships between characters to heighten this theme. Remember that what your characters have to fight for and what they stand to lose will be directly tied to the message you’re sending your readers. This will make the reader re-examine the things they’re fighting for in their own lives, in their society, and in the larger world around them.

Lastly, always write from a place of verisimilitude—from a place of true feelings, real questions, and human values, no matter how far-fetched the context of your world might be. When your readers are able to see themselves and their hopes reflected in your writing, that’s when it will stay with them forever.