You’ll often hear fiction writers talking about “character-driven stories”—stories where the strengths, weaknesses, and aspirations of the central cast of characters stay with us long after the book is closed. But what drives character, and how do we create characters that leave long-lasting impressions?

The answer lies in dialogue: the device used by our characters to communicate with each other. Powerful dialogue can elevate a story and subtly reveal important information, but poorly written dialogue can send your work straight to the slush bin. Let’s look at what dialogue is in writing, how to properly format dialogue, and how to make your characters’ dialogue the best it can be.

What is dialogue in a story?

Dialogue is the verbal exchange between two or more characters. In most fiction, the exchange is in the form of a spoken conversation. However, conversations in a story can also be things like letters, text messages, telepathy, or even sign language. Any moment where two characters speak or connect with each other through their choice of words, they’re engaging in dialogue.

Why does dialogue matter in a story?

We use dialogue in a story to reveal new information about the plot, characters, and story world. Great dialogue is essential to character development and helps move the plot forward in a story.

Writing good dialogue is a great way to sneak exposition into your story without stating it overtly to the reader; you can also use tools like dialect and diction in your dialogue to communicate more detail about your characters.

Through a character’s dialogue, we can learn about their motivations, relationships, and understanding of the world around them.

A character won’t always say what they mean (more on dialogue subtext below), but everything they say will serve some larger purpose in the story. If your dialogue is well-written, the reader will absorb this information without even realizing it. If your dialogue is clunky, however, it will stand out and pull your reader away from your story.

Rules for writing dialogue

Before we get into how to make your dialogue realistic and engaging, let’s make sure you’ve got the basics down: how to properly format dialogue in a story. We’ll look at how to punctuate dialogue, how to write dialogue correctly when using a question mark or exclamation point, and some helpful dialogue writing examples.

Here are the need-to-know rules for formatting dialogue in writing.

Enclose lines of dialogue in double quotation marks

This is the most essential rule in basic dialogue punctuation. When you write dialogue in North American English, a spoken line will have a set of double quotation marks around it. Here’s a simple dialogue example:

“Were you at the party last night?”

Any punctuation such as periods, question marks, and exclamation marks will also go inside the quotation marks. The quotation marks give a visual clue to the reader that this line is spoken out loud.

In European or British English, however, you’ll often see single quotation marks being used instead of double quotation marks. All the other rules stay the same.

Enclose nested dialogue in single quotation marks

Nested dialogue is when one line of dialogue happens inside another line of dialogue—when someone is verbally quoting someone else. In North American English, you’d use single quotation marks to identify where the new dialogue line starts and stops, like this:

“And then, do you know what he said to me? Right to my face, he said, ‘I stayed home all night.’ As if I didn’t even see him.”

The double and single quotation marks give the reader clues as to who’s speaking. In European or British English, the quotation marks would be reversed; you’d use single quotation marks on the outside, and double quotation marks on the inside.

Every speaker gets a new paragraph

Every time you switch to a new speaker, you end the line where it is and start a new line. Here are some dialogue examples to show you how it looks:

“Were you at the party last night?”

“No, I stayed home all night.”

The same is true if the new “speaker” is only in focus because of their action. You can think of the paragraphs like camera angles, each one focusing on a different person:

“Were you at the party last night?”

“No, I stayed home all night.”

She raised a single, threatening eyebrow.

“Yeah, I wasn’t feeling that well, so I just stayed in and watched Netflix instead.”

If you kept the action on the same line as the dialogue, it would get confusing and make it look like she was the one saying it. Giving each character a new paragraph keeps the speakers clear and distinct.

Use em-dashes when dialogue gets cut short

If your character begins to speak but is interrupted, you’ll break off their line of dialogue with an em-dash, like this:

“Yeah, I wasn’t feeling that well, so I just stayed in and—”

“Is that really what happened?”

Be careful with this one, because many word processors will treat your em-dash like the beginning of a new sentence and attach your closing quotation marks backwards:

“Yeah, I wasn’t feeling that well, so I just stayed in and—“

You may need to keep an eye out and adjust as you go along.

In this dialogue example, the new speaker doesn’t lead with an em-dash; they just start speaking like normal. The only time you’ll ever open a line of dialogue with an em-dash is if the speaker who’s been cut off continues with what they were saying:

“Yeah, I wasn’t feeling that well, so I just stayed in and—”

“Is that really what happened?”

“—watched Netflix instead. Yes, that’s what happened.”

This shows the reader that there’s actually only one line of dialogue, but it’s been cut in the middle by another speaker.

Each line of dialogue is indented

Every time you give your speaker a new paragraph, it’s indented from the left-hand side. Many word processors will do this automatically. The only exception is if your dialogue is opening your story or a new section of your story, such as a chapter; these will always start at the far left margin of the page, whether they’re dialogue or narration.

Long speeches don’t use use closing quotation marks until the end

Most writers favor shorter lines of dialogue in their writing, but sometimes you might need to give your character a longer one—for instance, if the character speaking is giving a speech or telling a story. In these cases, you might choose to break up their speech into shorter paragraphs the way you would if you were writing regular narrative.

However, here the punctuation gets a bit weird. You’ll begin the character’s dialogue with a double quotation mark, like normal. But you won’t use a double quotation mark at the end of the paragraph, because they haven’t finished speaking yet. But! You’ll use another opening quotation mark at the beginning of the subsequent paragraph. This means that you may use several opening double quotation marks for your character’s speech, but only ever one closing quotation mark.

If your character is telling a story that involves people talking, remember to use single quotation marks for your dialogue-within-dialogue as we looked at above.

Sometimes these dialogue formatting rules are easier to catch later on, during the editing process. When you’re writing, worry less about using the exact dialogue punctuation and more about writing great dialogue that supports your character development and moves the story forward.

How to use dialogue tags

Dialogue tags help identify the speaker. They’re especially important if you have a group of people all talking together, and it can get pretty confusing for the reader trying to keep everybody straight. If you’re using a speech tag after your line of dialogue—he said, she said, and so forth—you’ll end your sentence with a comma, like this:

“No, I stayed home all night,” he said.

But if you’re using an action to identify the person speaking instead, you’ll punctuate the sentence like normal and start a new sentence to describe the action taking place:

“No, I stayed home all night.” He looked down at his feet.

The dialogue tags and action tags always follow in the same paragraph. When you move your story lens to a new person, you’ll switch to a new paragraph. Each line where a new person speaks propels the story forward.

When to use capitals in dialogue tags

You may have noticed in the two examples above that one dialogue tag begins with a lowercase letter, and one—which is technically called an action tag—begins with a capital letter. Confusing? The rules are simple once you get a little practice.

When you use a dialogue tag like “he said,” “she said,” “he whispered,” or “she shouted,” you’re using these as modifiers to your sentence—dressing it up with a little clarity. They’re an extension of the sentence the person was speaking. That’s why you separate them with a comma and keep going.

With an action tag, you’re ending one sentence and beginning a whole new one. Each sentence represents two distinct moments in the story. That’s why you end the first sentence with a period, and then open the next one with a capital letter.

If you’re not sure, try reading them out loud:

“No, I stayed home all night,” he said.

“No, I stayed home all night.” He looked down at his feet.

Since you can’t hear quotation marks out loud, the way you say them will show you if they’re one sentence or two. In the first example, you can hear how the sentence keeps going after the dialogue ends. In the second example, you can hear how one sentence comes to a full stop and another one begins.

But what if your dialogue tag comes before the dialogue, instead of after? In this case, the dialogue is always capitalized because the speaker is beginning a new sentence:

He said, “No, I stayed home all night.”

He looked down at his feet. “No, I stayed home all night.”

You’ll still use a comma after the dialogue tag and a period after the action tag, just like if you’d separate them if you were putting your tag at the end.

If you’re not sure, ask yourself if your leading tag sounds like a full sentence or a partial sentence. If it sounds like a partial sentence, it gets a comma. If it reads like a full sentence that stands on its own, it gets a period.

External vs. internal dialogue

All of the dialogue we’ve looked at so far is external dialogue, which is directed from one character to another. The other type of dialogue is internal dialogue, or inner dialogue, where a character is talking to themselves. You’ll use this when you want to show what a character is thinking, but other characters can’t hear.

Usually, internal dialogue will be written in italics to distinguish it from the rest of the text. That shows the reader that the line is happening inside the character’s head. For example:

It’s not a big deal, she thought. It’s just a new school. It’ll be fine. I’ll be fine.

Here you can see that the dialogue tag is used in the same way, just as if it was a line of external dialogue. However, “she thought” is written in regular text because it’s not a part of what the character is thinking. This helps keep everything clear for the reader.

In your story, you can play with using contrasting internal and external dialogue to show that what your characters say isn’t always what they mean. You may also choose to use this internal dialogue formatting if you’re writing dialogue between two or more characters that isn’t spoken out loud—for instance, telepathically or by sign language.

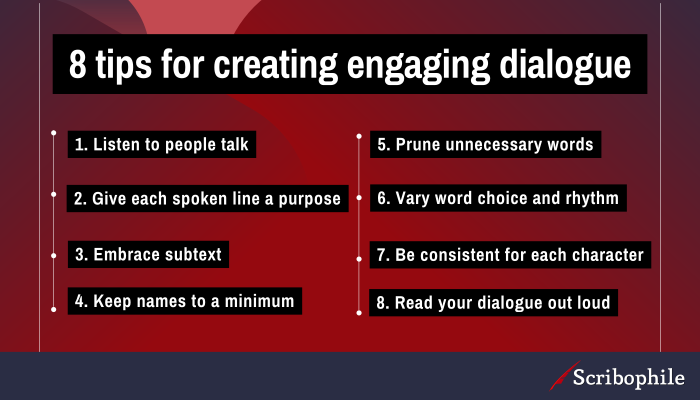

8 tips for creating engaging dialogue in a story

Now that you’ve mastered the mechanics of how to write dialogue, let’s look at how to create convincing, compelling dialogue that will elevate your story.

1. Listen to people talk

To write convincingly about people, you’ll first need to know something about them. The work of great writers is often characterized by their insight into humanity; you read them and think, “Yes, this is exactly what people are like.” You can begin accumulating your own insight by listening to what real people say to each other.

You can go to any public place where people are likely to gather and converse: cafés, art galleries, political events, dimly lit pubs, bookshops. Record snippets of conversation, pay attention to how people’s voices change as they move from speaking to one person to another, try to imagine what it is they’re not saying, the words simmering just under the surface.

By listening to stories unfold in real time, you’ll have a better idea of how to recreate them in your writing—and inspiration for some new stories, too.

2. Give each spoken line a purpose

Here is something that actors have drilled into their heads from their first day at drama school, and writers would do well to remember it too: every single line of dialogue has a hidden motivation. Every time your character speaks, they’re trying to achieve something, either overtly or covertly.

Small talk is rare in fiction, because it doesn’t advance the plot or reveal something about your characters. The exception is when your characters are using their small talk for a specific purpose, such as to put off talking about the real issue, to disarm someone, or to pretend they belong somewhere they don’t.

When writing your own dialogue, ask yourself what the line accomplishes in the story. If you come up blank, it probably doesn’t need to be there. Words need to earn their place on the page.

3. Embrace subtext

In real life, we rarely say exactly what we really mean. The reality of polite society is that we’ve evolved to speak in circles around our true intentions, afraid of the consequences of speaking our mind. Your characters will be no different. If your protagonist is trying to tell their best friend they’re in love with them, for instance, they’ll come up with about fifty different ways to say it before speaking the deceptively simple words themselves.

To write better dialogue, try exploring different ways of moving your characters around what’s really being said, layering text and subtext side by side. The reader will love picking apart the conversation between your characters and deducing what’s really happening underneath (incidentally, this is also the place where fan fiction is born).

4. Keep names to a minimum

You may notice that on television, in moments of great upheaval, the characters will communicate exactly how important the moment is by saying each other’s names in dramatic bursts of anger/passion/fear/heartbreak/shock. In real life, we say each other’s names very rarely; saying someone’s name out loud can actually be a surprisingly intimate experience.

Names may be a necessary evil right at the beginning of your story so your reader knows who’s who, but after you’ve established your cast, try to include names in dialogue only when it makes sense to do so. If you’re not sure, try reading the dialogue out loud to see if it sounds like something someone would actually say (we’ll talk more about reading out loud below).

5. Prune unnecessary words

This is one area where reality and story differ. In life, dialogue is full of filler words: “Um, uh, well, so yeah, then I was like, erm, huh?” You may have noticed this when you practiced listening to dialogue, above. We won’t say there’s never a place for these words in fiction, but like all words in storytelling, they need to earn their place. You might find filler words an effective tool for showing something about one particular character, or about one particular moment, but you’ll generally find that you use them a lot less than people really do in everyday speech.

When you’re reviewing your characters’ dialogue, remember the hint above: each line needs a purpose. It’s the same for each word. Keep only the ones that contribute something to the story.

6. Vary word choices and rhythms

The greatest dialogue examples in writing use distinctive character voices; each character sounds a little bit different, because they have their own personality.

This can be tricky to master, but an easy way to get started is to look at the word choice and rhythm for each character. You might have one character use longer words and run-on sentences, while another uses smaller words and simple, single-clause sentences. You might have one lean on colloquial regional dialect, where another sounds more cosmopolitan. Play around with different ways to develop characters and give each one their own voice.

7. Be consistent for each character

When you do find a solid, believable voice for your character, make sure that it stays consistent throughout your entire story. It’s easy to set a story aside for a while, then return to it and forget some of the work you did in distinguishing your characters’ dialogue. You might find it helpful to write down some notes about the way each character speaks so you can refer back to it later.

The exception, of course, is if your character’s speech pattern goes through a transformation over the course of the story, like Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady. In this case, you can use your character’s distinctive voice to communicate a major change. But as with all things in writing, make sure that it comes from intention and not from forgetfulness.

8. Read your dialogue out loud

After you’ve written a scene between two or more characters, you can take the dialogue for a trial run by speaking it out loud. Ask yourself, does the dialogue sound realistic? Are there any moments where it drags or feels forced? Does the voice feel natural for each character? You’ll often find there are snags you miss in your writing that only become apparent when read out loud. Bonus: this is great practice for when you become rich and famous and do live readings at bookshops.

3 mistakes to avoid when writing dialogue

Easy, right? But there are also a few pitfalls that new writers often encounter when writing dialogue that can drag down an otherwise compelling story. Here are the things to watch out for when crafting your story dialogue.

1. Too much exposition

Exposition is one of the more demanding literary devices, and one of the ones most likely to trip up new writers. Dialogue is a good place to sneak in some information about your story—but subtlety is essential. This is one place where the adage “show, don’t tell” really shines.

Consider these dialogue examples:

“How is she, Doctor?”

“Well Mr. Stuffington, I don’t have to remind you that your daughter, the sole heiress to your estate and currently engaged to the Baron of Flippingshire, has suffered a grievous injury when she fell from her horse last Sunday. We don’t need to discuss right now whether or not you think her jealous maid was responsible; what matters is your daughter’s well being. As to your question, I’m afraid it’s very unlikely that she’ll ever walk again.”

Can’t you just feel your arm aching to throw the poor book across the room?

There’s a lot of important information here, but you can find subtler ways to work it into your story. Let’s try again:

“How is she, Doctor?”

“Well Mr. Stuffington, your daughter took quite a blow from that horse—worse than we initially thought. I’m afraid it’s very unlikely that she’ll ever walk again.”

“And what am I supposed to say to Flippingshire?”

“The Baron? I suppose you’ll have to tell him that his future wife has lost the use of her legs.”

And so forth. To create good dialogue exposition, look for little ways to work in the details of your story, instead of piling it up in one great clump.

2. Too much small talk

We looked at how each line of dialogue needs a specific purpose above. Very often small talk in a story happens because the writer doesn’t know what the scene is about. Small talk doesn’t move the scene along unless it’s there for a reason. If you’re not sure, ask yourself what each character wants in this moment.

For example, imagine you’re in an office, and two characters are talking by the water cooler. How was your weekend, what did you think of the game, how’s your wife doing, are those new shoes, etc etc. Can’t you just feel the reader’s will to live slipping away?

But what about this: your characters are talking by the water cooler—Character A and Character B. Character A knows that his friend is inside Character B’s office looking for evidence of corporate espionage, so A is doing everything he can to stop B from going in. How was your weekend, what did you think of the game, how’s your wife doing, are those new shoes, literally anything just to keep him talking. Suddenly these benign little phrases have a purpose.

If you find your characters slipping into small talk, double check that it’s there for a purpose, and not just a crutch to keep you from moving forward in your scene. When writing dialogue, Make each line of dialogue earn its place.

3. Too much repetition

Variation is the spice of a good story. To keep your readers engaged, avoid using the same sentence structure and the same dialogue tags over and over again. Using “he said” and “she said” is effective and clear cut, but only for about three beats. After that, try switching to an action tag instead or letting the line of dialogue stand on its own.

You can also experiment with varying the length of your sentences or groupings of sentences. By changing up the rhythm of your story regularly, you’ll keep it feeling fresh and present for the reader.

Effective dialogue examples from literature

With all of these tips and tricks in mind, let’s look at how other writers have used good dialogue to elevate their stories.

Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine, by Gail Honeyman

“I’m going to pick up a carryout and head round to my mate Andy’s. A few of us usually hang out there on Saturday nights, fire up the playstation, have a smoke and a few beers.”

“Sounds utterly delightful,” I said.

“What about you?” he asked.

I was going home, of course, to watch a television program or read a book. What else would I be doing?

“I shall return to my flat,” I said. “I think there might be a documentary about komodo dragons on BBC4 later this evening.”

In this dialogue example, the author gives her characters two very distinctive voices. From just a few words we can begin to see these people very clearly in our minds—and with this distinction comes the tension that drives the story. Dialogue is an excellent place to show your character dynamics using speech patterns and word choices.

Pride and Prejudice, by Jane Austen

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?”

Mr. Bennet replied that he had not.

“But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.”

Mr. Bennet made no answer.

“Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently.

“You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.”

This was invitation enough.

“Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it, that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.”

In this famous dialogue example, the author illustrates the relationship between these two characters clearly and succinctly. Their dialogue shows Mr. B’s stalwart, tolerant love for his wife and Mrs. B’s excitement and propensity for gossip. The author shows us everything we need to know about these people in just a few lines.

Dinner in Donnybrook, by Maeve Binchy

“Look, I thought you ought to know, we’ve had a very odd letter from Carmel.”

“A what… from Carmel?”

“A letter. Yes, I know it’s sort of out of character, I thought maybe something might be wrong and you’d need to know…”

“Yes, well, what did she say, what’s the matter with her?”

“Nothing, that’s the problem, she’s inviting us to dinner.”

“To dinner?”

“Yes, it’s sort of funny, isn’t it? As if she wasn’t well or something. I thought you should know in case she got in touch with you.”

“Did you really drag me all the way down here, third years are at the top of the house you know, I thought the house had burned down! God, wait till I come home to you. I’ll murder you.”

“The dinner’s in a month’s time, and she says she’s invited Ruth O’Donnell.”

“Oh, Jesus Christ.”

This dialogue example is a telephone conversation between two people. The lack of dialogue tags or action tags allows the words to come to the forefront and immerses us in their back-and-forth conversation. Even though there are no tags to indicate the speakers, the language is simple and straightforward enough that the reader always knows who’s talking. Through this conversation the author slowly builds the tension from the benign to the catastrophic within a domestic setting.

Compelling dialogue is the key to a good story

A writer has a lot riding on their characters’ dialogue, and learning how to write dialogue is a critical skill for any writer. When done well, it can leaves a lasting impact on the reader. But when dialogue is clumsy and awkward, it can drag your story down and make your reader feel like they’re wasting their time.

But if you keep these tips in mind, listen to dialogue in your everyday life, and practice, you’ll be sure to create realistic dialogue that brings your story to life.