Pain is an unfortunate reality of human existence. So is experiencing, overcoming, inflicting, dreading, anticipating, and remembering it. But how do we effectively show these things in our writing?

It’s odd that something so universal is riddled with so many pitfalls for the emerging writer. When you explain a character’s pain in your novel or short story, you risk bogging down the narrative with cumbersome exposition, stretching your story’s credibility, or alienating your reader.

In this article, we’ll show you some helpful tips for how to show and describe pain authentically and smoothly in your writing (with some good examples from literature, too!).

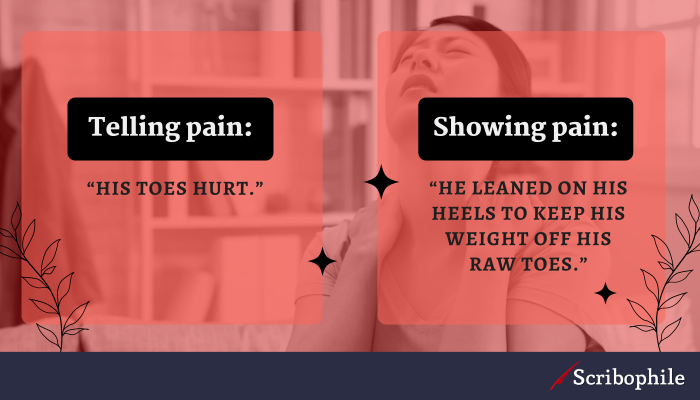

What does “show not tell” mean?

“Show, don’t tell” is a rule we hear a lot as writers. It means that instead of explaining something that’s happening, as if you were reciting a witness statement, it’s best to try and find visceral, engaging ways to illustrate what’s happening.

For example, telling the reader “her body hurt,” consider describing the way “her body dragged heavily with each step, the skin on one side a mottled canvas of red, irritated skin and green and purple bruises.”

At no point did we use words like “pain” or “hurt,” but as the reader you can imagine the character’s suffering clearly and distinctly.

Avoiding “telling” things to your reader as much as possible allows them to experience sensations—positive and negative—right beside your characters. This helps them feel more engaged with the story.

Physical pain vs. emotional pain

Your characters will probably experience both physical suffering and emotional distress at some point during your story. It may surprise you to know that the brain often processes emotional and physical pain in very similar ways.

For example, anxiety and heartache can lead to sharp chest and muscle pain, rawness in the throat, and difficulty breathing.

Despite what well-meaning friends might have you think, this isn’t just an illusory sensation; in extreme cases, emotional pain can even lead to a real heart attack—this is called stress cardiomyopathy, or “broken heart syndrome.”

When you’re writing about difficult emotions, consider the ways they might manifest in your characters’ bodies.

Likewise, physical pain has an adverse effect on our emotional state, too. Think about the emotional reactions your characters might have to physical suffering. If our bodies are damaged, we’ll probably be in a bad mood and may have trouble concentrating or remembering things.

Exploring the mental and emotional effects of physical pain can help you “show, not tell” the full scope of your character’s hurt.

Three levels of pain your characters may experience

A character’s pain isn’t a one-size-fits-all prescription. When you’re writing pain in a story, it’s important to consider the different types of experiences your characters may have.

Mild

We all experience mild pain at some point in our lives; it’s likely to be a common occurrence among your cast of characters. Mild pain includes things like aching backs, tired limbs, a fuzzy hangover headache, a cut that’s part way healed (we’ll look a bit more at healing processes below), or a sore throat.

These sorts of pains are present enough to be distracting—you don’t forget about them very easily—but they don’t inhibit you too much as you go about your day-to-day life.

In a story, you might use words like blunt pain or a dull, nauseating pain.

Mild pain can be from a physical stimulus—like stubbing your toe—a mental stimulus—like developing a headache after a stressful exam—or a combination of both mental and physical.

Showing the way mild pain and physical discomfort play a role in your character’s day is a good way of inviting the reader into their physicality.

Here’s an example of mild physical pain buffered by emotional pain from The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue, by V.E. Schwab:

The bottle slips through his fingers, shatters on the sidewalk, and he should leave it there, but he doesn’t. He reaches to pick it up, but he loses his balance. His hand comes down on broken glass as he pushed himself back up.

It hurts, of course it hurts, but the pain is dampened a little by the vodka, by the wall of grief, by his ruined heart, by everything else.

Here the narrator experiences the sharp pain of cutting glass, but it feels like a mild annoyance under all the emotional turmoil.

Moderate

Moderate physical pain is the next level on the pain scale, and this is the sort of discomfort that becomes a physical handicap.

If your legs are in moderate pain, you’ll probably have difficulty walking from one side of the room to another; if you have moderate chest pain, it will likely become more challenging to take deep breaths.

Moderate pain doesn’t stop a person from being active, but it will present a greater obstacle and make the activity more challenging.

While mental and emotional stimuli can exacerbate moderate pain—make it even more obtrusive and difficult to deal with—it usually comes from an external, physical source.

Here’s an example of moderate pain described in Magpie Murders by Anthony Horowitz:

I spent three days at the University College Hospital on the Euston Road, which actually didn’t feel nearly long enough after what I’d been through. But that’s how it is these days: the marvels of modern science and all that.… I couldn’t stop coughing and I hated it. My eyes still hadn’t cleared up. This was fairly common after a head injury but the doctors had warned me that the damage might be more permanent.

Rather than lamenting her suffering, the narrator takes an objective approach to showing the circumstances around her pain. The first line implies the severity of the experience without putting pain front and center.

The details show the reader that while the discomfort is still debilitating, the protagonist is able to manage the motions of their day.

Severe

Extreme pain is the one we tend to read about most often, but encounter least often in real life. This level of pain becomes a handicap and prevents the character from taking all the actions they normally would.

For example, someone experiencing a severe headache (rather than a moderate one) might not be able to see or hear clearly; someone experiencing severe bodily pain might not be able to use one or more of their body parts—for instance, not being able to use their arm after it was recently broken.

In a story, this might be described as a stabbing pain or a searing pain, rather than a dull ache.

Here’s an example of severe pain being inflicted in If We Were Villains, by M.L. Rio:

The pommel and guard cracked across my face, white-hot stars burst through my field of vision, and pain hit me like a battering ram. Camilo and one of the soldiers shouted at the same time. The rapier slipped loose from my fingers and cracked down beside me as I fell backward onto my elbows, blood gushing from my nose like someone had turned on a faucet.

Notice how the moment begins with a wide lens—the physicality of the action—and then slowly moves closer to the character’s own feelings. Instead of saying “I was in blinding agony,” the narrator describes his movements with a specificity that shows the reader what they must be going through.

Although it can be tempting to put your heroes in severe pain all the time, remember that your readers can become desensitised to these moments if you lean into them too often.

If your hero is constantly getting stabbed and slashed and getting various limbs torn apart by beasties, at some point the reader is going to feel their will to care evaporate; the pain no longer feels important.

To get the greatest impact when you describe pain in your writing, think of the 3—2-1 rule: For each character, show mild pain three times throughout the story, moderate pain twice, and severe pain just once. This will make your scenes feel more realistic and engaging to the reader.

Tips for showing pain in your story

Now that we understand a bit more about the pain thresholds you might explore in a story, here are a few tips to take your writing to the next level.

Turn your character’s pain into an obstacle

The moment a character is hurt isn’t just a singular experience; it impacts their movements, abilities, and choices for the near to semi-distant future. To write pain convincingly, show how your character needs to navigate life through and around it.

In the above example from When We Were Villains, the protagonist has to deal with the effects of his pain for weeks afterward. In one moment, he says:

A sneeze began to form under the splint on my nose, and for a moment I didn’t dare breathe, afraid of how much it would hurt.

This shows the reader how his pain is a constant obstacle that he’s having to account for as he moves through the plot.

Other examples might be showing how they learn to rely on their non-dominant hand; how they use their environment in new ways for balance or mobility; or how they learn to pay more attention to other senses if one of their senses has become impaired.

Being in pain is a little bit like having a rather unpleasant pet. Slowly, you learn how to predict its moods and ways to accommodate for its presence.

Give the pain its own character arc

Pain, even chronic pain, is not constant. There will be moments when it feels horrific and moments where it feels more manageable.

If your protagonist’s pain is inflicted through some external source, such as an injury, the character arc of the suffering will probably be fairly linear—worst at the onset, and then slowly better over time.

However, there may be moments during the healing process where the body doesn’t have the energy to fight off the pain, or when certain medications have worn off, or when some external experience triggers the pain back into being—such as accidentally putting pressure on a flesh wound.

In this case you might say your protagonist “felt fresh pain sear before settling into a dull throb.” When you describe pain as more than one static sensation, you show your reader the way it becomes a living, breathing thing.

Some characters may even experience a “phantom pain,” which is where the body psychosomatically remembers an injury even after it’s healed. This is common in traumatic injuries such as what a soldier may have experienced in a war.

Sometimes phantom pains can become enmeshed in personal folklore, like when a former soldier claims his right shoulder hurts just before it rains.

If your character’s pain is chronic or the result of an illness, it will probably fall into a pattern of ebbing and flowing. To bring your characters’ pain to life, remember to let them experience all the different ways this pain manifests itself throughout the story.

Treat your characters as human

Remember to acknowledge the natural limitations your characters have as people. If your Bond-like hero is constantly getting shot, beaten, and broken and still manages to leap onto a car two stories below and walk away, you’re going to lose your audience.

If your characters’ injuries aren’t having a real, measurable impact, they become nothing more than costumes.

This is true even for characters that aren’t technically human, or human in the way we understand—such as mythical creatures or superheroes. Their limitations may be different than ours, but they will still have a breaking point.

It’s up to you as the writer to determine where that is, keep it consistent, and then show what happens when your character is pushed across it.

Even if your characters are all the same species, you may discover that they don’t all experience or feel pain in the same way. For instance, gender can play a role in the way a character suffers and how much pain they can endure. Women are biologically known to be more pain tolerant due to childbirth and menstruation, while men are more often put in physically stressful environments.

Different professions can also impact a character’s relationship with pain, both in themselves and others.

When crafting your cast of characters, remember to not only define their limitations, but to define the limitations of each one as an individual.

Find the right words to show, don’t tell pain in a story

Every good story has at least one scene where a character is hurt—whether that’s physically, emotionally, or some blend of the two. When you learn how to write pain convincingly and authentically, you make your story feel that much more immersive and intimate to the reader.